Jottings about some of the things that keep me amused in my spare time, either observations or items of a creative or constructive nature... (This does not include much about British birds. And you've probably come to the wrong place if you're expecting titillation of any kind!)

Tuesday, 1 December 2020

Liquitex Medium Viscosity acrylic paints

The original format bottles were widely-sold. I bought examples from WH Smith’s in the UK; in an office supplies store in Montreal, Canada; and a local art supplies shop in Oxford, England. They were (and are) excellent paints, being heavily-pigmented and ready for immediate use. (No shaking or stirring necessary.) The screw-on cap with flip-off lid made them very convenient to use. There must have been a large number of colours in the range at its zenith; appealing to artists, crafters and model makers. So why did they disappear from the shops?

Probably only Liquitex themselves know the answer. But I suspect that there are a number of reasons. Cheap imports, competing ranges and more specialised paints.

One other point. The selection shown here includes colours that no longer appear in the current Liquitex ranges. To be honest, I can't think of an obvious use for Christmas Green, but Taupe appealed to me as a scenic colour, and Polished Steel is very useful on models and miniature figures. Christmas Green sounds like a craft colour, and Polished Steel sounds like a hobby colour, so I am guessing that Liquitex stopped producing their craft and hobby colours in order to focus on their art colours?

Sunday, 1 November 2020

Malayan butterflies

Thursday, 1 October 2020

Origami

In many ways, I was brought up like my parents were — especially when younger. They were children of the 20th century inter-war years, long before television, computers and mobile phones were common in most households or even invented! In those days it was generally expected that children would make their own entertainment. They were encouraged to read books, take up hobbies and play outside when the weather permitted. Thousands of British young people were raised in a similar way. Were they deprived or disadvantaged because they didn’t enjoy the trappings of the UK in the 21st century? No, far from it! They have since been called our Greatest Generation, because they brought us through the trials of the Second World War and its aftermath, and thanks to their achievements we enjoy life as it is today.

In the early 1970s I could already list things like reading, Airfix kit-building, Lego and stamp collecting as hobbies and pastimes. (I even had a spell as a butterfly collector!) It must have been my friend John in Junior School who introduced me to Origami, the Japanese art of paper folding. Like several things in the 1970s, it was a bit of a thing at the time, no doubt encouraged by a programme on television hosted by Robert Harbin.

What appealed to me was that all you needed was a simple square of paper and a few minutes of time. And the ability to follow instructions carefully and make accurate folds. There were at least two books published at the time as a companion to the TV series, which were a great help. It was even possible to buy special Origami paper in bold colours, but I seem to remember that it was relatively expensive on my modest pocket money budget of the time!

Nearly half a century later, I can still remember the important folds and bases, and produce an acceptable Flapping Bird in a few minutes! Once upon a time, I could even make the amazing 3D Jackstone (by Jack Silverman of the USA?) from memory; but that was nearly three decades ago and my brain has been filled with other things since!

Tuesday, 15 September 2020

Spitfire at RAF Biggin Hill

On the 80th anniversary of Battle of Britain Day, I thought this would be an  appropriate subject. Back in June 1992, some family friends who were stationed at RAF Biggin Hill at the time invited my mother and I to experience the Biggin Hill Airshow from the RAF side of the airfield. Despite its history and association with the Battle of Britain in particular, I was sadly aware that RAF Station Biggin Hill was due to close in October of that year. This was my opportunity to record something of the Station before closure.

appropriate subject. Back in June 1992, some family friends who were stationed at RAF Biggin Hill at the time invited my mother and I to experience the Biggin Hill Airshow from the RAF side of the airfield. Despite its history and association with the Battle of Britain in particular, I was sadly aware that RAF Station Biggin Hill was due to close in October of that year. This was my opportunity to record something of the Station before closure.

The weather was perfect for an airshow, and armed with camera and films I soon shot through my colour exposures on the aerial displays. I still had rolls of black and white Kodak Plus X Pan, and carried on shooting that as the day came to an end. The colour film was duly processed and when I treated myself to a flatbed scanner in 2010, some of those photos became part of my Flickr stream. However, the black and white exposures were put away in the fridge to be processed at a later date...

It was August 2016 when I decided that I ought to do something about the exposed and unprocessed films in my fridge! The film itself would have expired in early 1983 (bulk-loaded), and I had not recorded when it had been exposed, so I picked one at random. This turned out to be the Biggin Hill film from 1992. I had it commercially processed in Oxford rather than doing it myself.

When I received the negatives, the good news was that there were images on the film. The less good news was that they were of low contrast and showed some fogging due to age, so it would be a challenge to extract usable images from them. Although the de facto standard software for doing this is Adobe Photoshop, I prefer to use GIMP (GNU Image Manipulation Program) due to licensing and cost reasons. I don’t have a record of how many hours I spent experimenting with both scanner software and GIMP settings, but I now have a better idea of how to get the best results from my scanning! Eventually, I found that repeated use of Layers resulted in a smoother and brighter sky.

Had I captured a historic moment? Was this the last time that an iconic Spitfire was serviced at RAF Biggin Hill? (Probably not, as this would have likely continued till the end of the air display season.) The hangar to the right is no more, but remarkably the concrete surface on which the Spitfire stands and the walls behind it still exist (as of early September 2019). I believe these are what remain of the Belfast triple-bay hangar that was demolished on the orders of the RAF Biggin Hill Station Commander on 4th September 1940, after a number of devastating Luftwaffe air raids during the Battle of Britain.

Some 80 years later, Biggin Hill Airport as it is now, still occasionally reverberates to the sounds of Spitfires. We are most fortunate to live in more peaceful times. And we should still be grateful for the young men and women who gave their best (and in some cases gave their lives) when most of the free world needed them.

Saturday, 1 August 2020

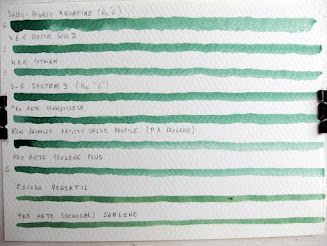

Pro Arte Sablene brushes

Within the last couple of years, I noticed that Ken Bromley Art Supplies has been selling a Pro Arte brush called Sablene. Tantalisingly, little additional information seems to be available about it, and few people seem to have tried one and posted their reactions. I wondered whether Sablene might be the response to the Escoda Versatil and other synthetic brushes that claim to give a more sable-like experience when painting?

What is even more mysterious is that as of late July 2020, Pro Arte’s own Website makes no mention of Sablene whatsoever! (Or of Sablesque, which appeared about the same time as Sablene.) Odd.

Ken Bromley's only supplies these brushes in wallets containing four or five different brushes: you cannot (yet?) buy brushes individually. Also, there are some wallets described as Scholar, which are a little cheaper but the brushes have silver-coloured ferrules rather than gold-coloured. (Guess which sort I bought?...) Yes, I chose the Scholar 38WA pack containing Nos. 2, 4, 6, 8 round, and a 3/8 inch flat. I hoped that the cost would be saved in the handles and the hairs would be the same quality as in the more expensive wallets...

The brushes arrived in the same order as the Van Gogh paints I mentioned previously. To start with, I thought I would add to the test of brushes I made in February 2015 to get some idea of performance. As I said back then, this is totally unscientific, and is simply a crude way of seeing how much paint a brush will hold and how well it releases it onto the paper.

Monday, 13 July 2020

Van Gogh watercolours

During one late evening Internet browsing session during the COVID-19 lockdown, I discovered that Ken Bromley Art Supplies now carry the Royal Talens Van Gogh range of student watercolour paints. Could these be a viable alternative to my favoured Cotman watercolours? Would EU manufacture win out over Far Eastern? Attracted by the reasonable pricing and the availability of some single pigment paints that are normally only available in more expensive artists’ ranges — and swayed by some favourable reviews — I ordered four 10 ml tubes. (Ken Bromley doesn’t stock these paints in pans.)

During one late evening Internet browsing session during the COVID-19 lockdown, I discovered that Ken Bromley Art Supplies now carry the Royal Talens Van Gogh range of student watercolour paints. Could these be a viable alternative to my favoured Cotman watercolours? Would EU manufacture win out over Far Eastern? Attracted by the reasonable pricing and the availability of some single pigment paints that are normally only available in more expensive artists’ ranges — and swayed by some favourable reviews — I ordered four 10 ml tubes. (Ken Bromley doesn’t stock these paints in pans.)Despite the effects of the pandemic, my order was delivered to my door within four days, which I thought was good going. I had chosen a tube each of Raw Sienna, Sap Green, Pyrrole Orange and Azomethine Green Yellow. My only previous experience with student watercolours (ignoring the cheap rubbish in tin boxes that I remembered from childhood) has been with the Winsor and Newton Cotman range, so I was curious to try them out right away.

It has become standard procedure for me with any new watercolour paint, to make a small square reference swatch on a 1/16 Imperial sheet of Fabriano 130 lb Watercolour paper. (Making sure I label each one with the brand and colour.) This is a useful way of seeing which paints I own and gives some idea of what the paint will look like on paper — but it is not the best way to compare different paints. (The Internet has a number of excellent suggestions of how to organise ones watercolour paint swatches!)

All the Van Gogh tubes were well-filled with paint, and in the case of the Sap Green and Azomethine Green Yellow, I had to be careful not to make a mess of the cap and threads. I dabbed a little paint into my porcelain mixing dish and gradually added water with a paint brush till I had what I thought was a medium intensity. Each of the paints seemed a little reluctant to dilute with water and achieving an even mix seemed like more effort than I was used to with Cotmans. When painting out the swatches, I was surprised to see some bronzing in the Sap Green — so I must have mixed it stronger than I thought. The Raw Sienna came out a little weak and patchy. Both the Pyrrole Orange and Azomethine Green Yellow worked as expected, however.

It was at this point that I decided to consult the Internet — something I should have done before I placed my order! Granted, there were some favourable reviews, notably by people who had been sent sets by Royal Talens — including one who used rather expensive paper (Hahnemühle Leonardo 300 lb no less!). But I found one or two comparative reviews more helpful and balanced. Comments like saturated, low flow, some bronzing, no chalkiness, easy re-wetting, opaqueness, optical brighteners, and muddled colour seemed to be a common theme. I was a bit concerned that the author of the Scratchmade Journal wrote that I like to build watercolor paintings in gentle layers, but Van Gogh doesn't go for that. This watercolor likes to go down strong and be left alone, but I did enjoy using them similar to gouache.

I read that to mean that Van Gogh watercolours were not suitable for glazing techniques — something I believe is fundamental to watercolour. Elsewhere, I read a grumble that the paints could not be overpainted without lifting, which if true meant that the paints would be in large part useless to me! I had already noticed the reluctance to flow, but I found the reports of ease of rewetting more troubling. I decided to perform a simple test. If I painted out a square of Pyrrole Orange (which I know is staining in other brands) wet on dry, how would it respond to glazing and lifting?

Well, despite using (St Cuthbert’s Mill) Bockingford 300 gsm CP paper which is known for its colour-lifting ability, I was pleased to find that repeated scrubbing with water and a Pro Arte Prolene Plus round brush lifted very little colour after a day. A glazing test using Cotman Ultramarine worked perfectly. And a subsequent glazing test a day later using Van Gogh Azomethine Green Yellow (diluted with homemade distilled water) didn’t cause disappointment either, even on the Cotman Ultramarine which usually lifts fairly easily.

Well, despite using (St Cuthbert’s Mill) Bockingford 300 gsm CP paper which is known for its colour-lifting ability, I was pleased to find that repeated scrubbing with water and a Pro Arte Prolene Plus round brush lifted very little colour after a day. A glazing test using Cotman Ultramarine worked perfectly. And a subsequent glazing test a day later using Van Gogh Azomethine Green Yellow (diluted with homemade distilled water) didn’t cause disappointment either, even on the Cotman Ultramarine which usually lifts fairly easily.Therefore, I am happy to say that despite some initial misgivings, my testing has shown that at least two of my paint choices work in the way I would expect them to, and they will be a useful addition to my watercolour palette. I will look into improving the paint flow: the distilled water seemed to help a little. (My tap water is fairly hard.)

I think this goes to show that we all have different expectations and ways of working. I have the greatest admiration for someone who can produce a masterpiece in a couple of hours or less; my approach is more measured and deliberate. (It is a hobby for me.) I would certainly consider using Van Gogh paints again in the future. But I don’t think they will replace my Cotmans. Perhaps I was fortunate with my choices? (Except for the Raw Sienna...)

Monday, 1 June 2020

Canon EOS digital colour 3

Perhaps predictably, after about a year I became dissatisfied with the colour in the photos I was getting from my Canon EOS 100D, using my variation of the Prolost Flat setting. I mostly shoot landscapes as both a record of where I have been, and/or as a record of how my world is changing, and I felt that there was still something lacking. In one comparison shot with my favoured compact camera, I was disappointed and surprised to see how much the sky differed between the two cameras. Had I overdone the Auto White Balance (AWB) setting on the EOS that badly?

Perhaps predictably, after about a year I became dissatisfied with the colour in the photos I was getting from my Canon EOS 100D, using my variation of the Prolost Flat setting. I mostly shoot landscapes as both a record of where I have been, and/or as a record of how my world is changing, and I felt that there was still something lacking. In one comparison shot with my favoured compact camera, I was disappointed and surprised to see how much the sky differed between the two cameras. Had I overdone the Auto White Balance (AWB) setting on the EOS that badly? Once again the video people on the Internet confirmed what I had been seeing: the Canon Neutral colour setting produces strong greens and magenta in the blues! So Neutral colour was actually turning my distinct blue skies to washed-out blue-grey, and also doing strange things to the colours of the clouds. (Apparently the Canon Faithful colour setting is similar to Neutral but boosts the reds.) So no wonder that my picture of the ruined Corfe Castle on a sunny summer afternoon failed to draw my eye afterwards.

Once again the video people on the Internet confirmed what I had been seeing: the Canon Neutral colour setting produces strong greens and magenta in the blues! So Neutral colour was actually turning my distinct blue skies to washed-out blue-grey, and also doing strange things to the colours of the clouds. (Apparently the Canon Faithful colour setting is similar to Neutral but boosts the reds.) So no wonder that my picture of the ruined Corfe Castle on a sunny summer afternoon failed to draw my eye afterwards. Given that most of the other Canon camera picture modes influence the colour in known ways, the obvious choice was to return to the Standard colour mode setting. Thanks to previous camera forum comments and my own experiments, I knew that the contrast needed to be turned right down. I also knew that the saturation had to be reduced below zero to tone down the colours: I experimented with -2 and -1 saturation before settling on -1. I increased the sharpness by one to 4, which is probably as high as I dare risk it going by other Internet comments. Lastly, I tweaked the Auto White Balance compensation to A3 + G2. I think this is now pretty close to what I am expecting to see. (See the top image. For comparison, the second image was taken within a few seconds of the first and shows what my variation of Prolost Flat looks like using A4 + G4 AWB. Hmm, no surprise that I thought there was something missing...)

To summarise, the settings I am now using are (S, 4, -4, -1, 0), with A3 + G2 AWB. I know that most other people who care about this sort of thing “shoot raw” — but someone might find this useful.

Monday, 11 May 2020

Modelu figures 2

I have been one of the fortunate people — even though I may not always think it — who has been able to work safely from home during the UK COVID-19 lockdown, albeit everything seems to take at least 50 percent longer and my working day is invariably lengthened! Given that I now need to make time for exercise that I would normally get during the daily commute to work, I don’t actually have any additional time to myself during the week. Even weekends seem to have filled up with Zoom sessions and the like!

I have been one of the fortunate people — even though I may not always think it — who has been able to work safely from home during the UK COVID-19 lockdown, albeit everything seems to take at least 50 percent longer and my working day is invariably lengthened! Given that I now need to make time for exercise that I would normally get during the daily commute to work, I don’t actually have any additional time to myself during the week. Even weekends seem to have filled up with Zoom sessions and the like!Nevertheless, I was determined to attempt at least one rainy-day project, and thought that the Modelu figures that I reviewed back in March 2017 might be something achievable in small doses. I would use the same painting technique that I mentioned in January 2015 that worked well on cast metal figures. Would I be satisfied with the results on plastic 3D-printed figures?

The first step was to take each figure and carefully wash it with warm water and inexpensive shower gel, using an old soft-bristled craft paint brush. Once all the figures had been washed, they were left in a warm dust-free environment for at least 24 hours to dry. I was then able to use double-sided tape (3M) to carefully attach (without handling) each of the figures to an old scrap of softwood, in preparation for the matt black base coat.

My favoured way of applying the black paint layer is to use acrylic matt black from an aerosol can, as is usually found in car accessory shops and similar. It is important that this is done outside on a still, fine day, or else in a shed where the vapour can be directed outside! The trick is to go for two or three light applications of paint, allowing ten minutes between each coat.

The figures in their black paint undercoats can then be returned to their warm, dust-free environment for at least another 24 hours to allow the base coats to harden. (I found that an inverted 0.3 litre Really Useful Storage box and lid made an ideal drying area.)

The next stage required each figure to be carefully removed from the block of wood and attached to an individual base for brush-painting. I found that old orange juice carton caps and milk container caps worked well as a source of bases. The double-sided tape still had enough tack to fix the bases of the figures to the caps. I used more double-sided tape to attach a couple of coins inside the milk cap to give more stability to the 0 gauge figure.

Now I could start on the hand-painting. I began with Daler-Rowney Warm Grey System 3 acrylic paint, dry-brushed on to each figure in turn using a Pro Arte Acrylix Series 204 flat brush — 1/8” for the 4 mm scale figures, and 1/4” for the 7 mm figure. Strokes were always vertically downward, attempting to recreate the shadows of strong light from above. Allowing at least 24 hours for the grey to harden, I repeated the process more sparingly with Daler-Rowney Titanium White in order to depict the high-lights on the upper surfaces of each figure.

Tune in another time to see progress on the glazes, and hopefully the finished articles...

Tuesday, 21 April 2020

Their finest hour

In these strange and uncertain times, I post a photo of the interior of the Saint George’s RAF Chapel of Remembrance at Biggin Hill in Kent, England. As some people might know, RAF Station Biggin Hill as it was then, played a key part in the summer of 1940 during the Battle of Britain. Its fighter pilots fought with distinction against the Luftwaffe, and were ably supported by courageous ground crews and station personnel who kept things going despite a number of devastating air raids.

In these strange and uncertain times, I post a photo of the interior of the Saint George’s RAF Chapel of Remembrance at Biggin Hill in Kent, England. As some people might know, RAF Station Biggin Hill as it was then, played a key part in the summer of 1940 during the Battle of Britain. Its fighter pilots fought with distinction against the Luftwaffe, and were ably supported by courageous ground crews and station personnel who kept things going despite a number of devastating air raids.The Battle of Britain has passed into legend as one of the times when the UK has prevailed in times of adversity, along with the myths that the Spitfire won it and the RAF was outnumbered. (The facts are a little different!) Thanks to the vision and preparation before the Second World War of the head of the RAF’s Fighter Command — Air Marshall Dowding — the Royal Air Force’s squadrons of Hurricanes and Spitfires were up to the job of keeping the Luftwaffe from British skies during daylight hours (when it could have done the most damage). Dowding — as a former fighter pilot himself — took a keen interest in the needs of his pilots (his chicks), and knew that they would be at the sharp end of things. Therefore, anything that could be done to protect his pilots (bulletproof windscreens, seat back armour) or give them an advantage (higher octane fuel, DeWilde ammunition) was organised. Then of course, there was the Dowding System, the world’s first co-ordinated air defence system.

So what’s this got to do with the COVID-19 pandemic? Well, unlike the mid- and late-1930s, it seems that in the Western Hemisphere, no-one saw this coming — or else decided the risk was too small to bother with. So we have frontline medical workers (the fighter pilots of today) working long hours, exposing themselves to high levels of Coranavirus, and struggling to source effective Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), despite repeated assurances from the UK government that this is under control. Can you imagine pilots bolting-on protective windscreens and armour plate to their fighter aircraft in 1940? Or taking off without oxygen masks?

In 1940 the UK had a mature RDF (Radar) and tracking system to show when and where the threat was likely to come from. Still as of today, the UK has limited Coronavirus testing, and no case tracking scheme that I am aware of. How is it possible to contain the spread of the disease and return to normality in a reasonable amount of time if no-one knows where the cases are? Or who has already had it (and has not been to hospital)?

My heart goes out to all frontline workers, facing an enemy they cannot see with the uncertainty of the harm it will cause.

I would like to think that this is a wake-up call for the planet, but the signs are that the world leaders still don’t understand the message. May you live in interesting times...

Sunday, 1 March 2020

Using NIS with OpenLDAP on a server

Network Information Service (NIS) — formerly known as Yellow Pages (YP) — is an information sharing technology developed by Sun Microsystems in the 1980s for the Unix Operating System. Despite the introduction of an improved system named NISplus in the 1990s, the use of NIS persisted, and became supported by the Linux Operating System as well as Unix. When the time came to upgrade NIS to a more capable technology, the system of choice was often Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP), or (ironically) Microsoft’s Active Directory (AD).

Network Information Service (NIS) — formerly known as Yellow Pages (YP) — is an information sharing technology developed by Sun Microsystems in the 1980s for the Unix Operating System. Despite the introduction of an improved system named NISplus in the 1990s, the use of NIS persisted, and became supported by the Linux Operating System as well as Unix. When the time came to upgrade NIS to a more capable technology, the system of choice was often Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP), or (ironically) Microsoft’s Active Directory (AD).

Saturday, 1 February 2020

The 30 minute artist

I first heard about the artist Terry Harrison when I was given a useful book about acrylic painting techniques a few Christmases ago. (Despite its modest cost, the book was my favourite gift that year, if I had to chose one.) I subsequently learnt that Terry was an accomplished painter, and did much to promote painting through tutorials, classes and even his own range of brushes and paints. And a number of books, of course. It was therefore with some dismay and sadness that I learnt that Terry had succumbed to cancer two and a half years ago, while still in his 60s. He seemed like a gentle and kind person.

I first heard about the artist Terry Harrison when I was given a useful book about acrylic painting techniques a few Christmases ago. (Despite its modest cost, the book was my favourite gift that year, if I had to chose one.) I subsequently learnt that Terry was an accomplished painter, and did much to promote painting through tutorials, classes and even his own range of brushes and paints. And a number of books, of course. It was therefore with some dismay and sadness that I learnt that Terry had succumbed to cancer two and a half years ago, while still in his 60s. He seemed like a gentle and kind person.More recently, I was tempted into buying a pad of all-cotton watercolour paper from Ken Bromley Art Supplies, and the book Painting Water in Watercolour by Terry Harrison also caught my eye. The price was under a tenner, and as I appear to have included water in a number of my (few) paintings, I thought it might help me in the future if the inclination continues. Perhaps there would be a technique I could try after a number of months of painting inactivity?

My package arrived from Ken Bromley well-packed and in no time at all -- the usual excellent levels of service. The watercolour pad was squirreled-away for a time when I feel I will be able to do the paper justice. The book was a little smaller than I expected, at 96 pages. I was hoping it might have been hardcover with a spiral binding like my acrylic book, but it was a standard softcover and glued binding. However, the content itself did not disappoint.

Inside were sections on materials, colours, techniques and projects. (Apart from the projects, not unlike my earlier acrylic book really.) As the book's subtitle suggests, the idea is that any of the projects can be completed in 30 minutes if you follow Terry's instructions -- and are as adept and proficient as Terry was, of course! I think this is a good idea in principle, as many people have full and busy lives, and taking more than an hour out to paint can be a big ask.

Suitably inspired and wanting to try out a WHSmith Watercolour Paper pad that I had received for Christmas, I thought that there might be an exercise I could do. Sure enough, the Sky reflections technique on page 54 seemed to fit the bill, as it seemed reasonably simple and mostly within my capabilities; also, it looked effective as a painting in its own right.

The book shows an image for each step with text underneath: the text says what you need to do for that step, including suggestions as to which brush(es) to use and which colour(s). I tried to match the brush selections from my collection. The recommended colour palette was Raw Sienna, Ultramarine and Burnt Umber. I used Cotman colours throughout, but substituted Cadmium Yellow Pale Hue (with a touch of Cadmium Red Pale Hue in places) for the Raw Sienna. Otherwise, I followed the instructions as closely as I could.

The (uncorrected) result is shown here, warts and all! It took me around 45 minutes in total, allowing time for the paper to dry between two of the steps. (I imagine that Terry would have been able to do this comfortably in about ten minutes using a hairdryer.) As I suspected, the paper did not really lend itself to wet-in-wet painting, but nor did it cockle too badly either. I am pleased with how it turned out, given the unfamiliar paper and lack of prior practice. But clearly I need to work on my technique (and my observations!) if I am to achieve more convincing reflections in water... (Can I say Axis of Symmetry?)

The (uncorrected) result is shown here, warts and all! It took me around 45 minutes in total, allowing time for the paper to dry between two of the steps. (I imagine that Terry would have been able to do this comfortably in about ten minutes using a hairdryer.) As I suspected, the paper did not really lend itself to wet-in-wet painting, but nor did it cockle too badly either. I am pleased with how it turned out, given the unfamiliar paper and lack of prior practice. But clearly I need to work on my technique (and my observations!) if I am to achieve more convincing reflections in water... (Can I say Axis of Symmetry?)Terry Harrison's book is definitely worth having if you are learning to paint in watercolour and expect to depict some sort of water (lake, stream, sea, puddle, waterfall) in at least one of your pictures. Fortunately, being a 30 minute artist is optional.

Wednesday, 1 January 2020

No nuts please, we’re British?

A Happy New Year to all my non-existent readers!

A Happy New Year to all my non-existent readers!On a seasonal note, I am still partial to a little Christmas pudding at this time of year. Over time, tastes seem to have changed, and the sweet course of mince pies and Christmas pudding may be skipped altogether — or there might be an alternative dessert. I suspect that the rich fruit and pastry are not to everyone’s liking now. As a reasonably young person, Christmas pudding was the highlight of the festive meal and I recall that sometimes a second helping was out of the question as it had all been eaten!

In the mid-1970s I moved to Canada. I soon discovered that nuts were a lot more common in cakes and confectionery than I had been used to. They even put them in ice cream! I couldn’t see the point: I disliked nuts, and could not see the pleasure in their hardness and bitterness. (Although I did like savoury peanuts and cashew nuts.) Thankfully I never had a nut allergy.

The first time I was aware of nuts in a Christmas pudding must have been the early 1980s. My father had been given a homemade Christmas pudding by someone he knew, and I’m sure we were told that it was rather good. Well, expecting wonderful things, both my parents and I were disappointed to be munching through significant quantities of nuts, and much adverse comment and moaning ensued! My father spared us from the ordeal of a repeat helping of the unfortunate pudding, when with good intentions he attempted to reheat it in our relatively new microwave oven and somewhat overestimated the time required. Result: one rather charred and inedible pudding! Phew.

But this was only a portent of what was to come. Some 30 years later, and back in the UK, we seem to have become North Americanised (globalised?). Noticeable quantities of nuts are now standard ingredients in our so-called traditional Christmas puddings. Pecans? Come on! The Waitrose one pictured above is a typical example, regrettably.

I don’t dispute that nuts may have always been a key ingredient of Christmas pudding, but back in the day they were chopped or crushed finely enough that you were not aware that you were eating them. I don’t think we even knew what pecans were in the 1970s! So if the manufacturers insist on putting nuts in, make sure they are finely chopped, dammit.